Are subcultures dead?

Is that even possible?

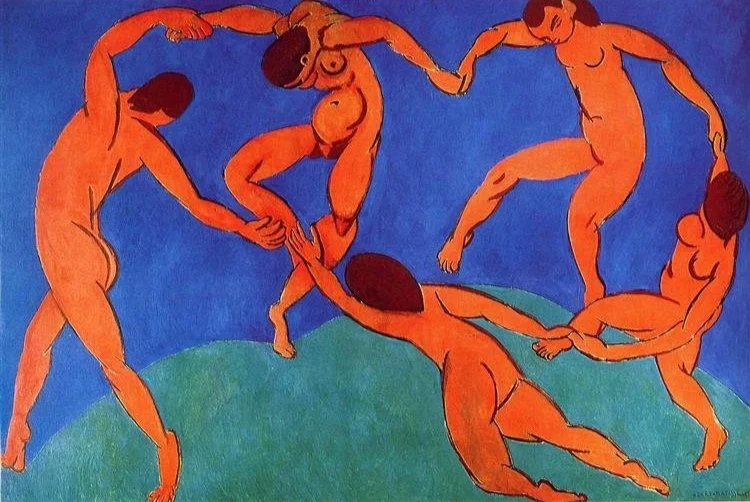

Henri Matisse’s “Dance” is often associated with community, emotional liberation, and of course, music.

Ever since the rise of the internet, there have been cries of the death of subcultures. Lamentations that “things are not like in the good old days” and “this generation will never know true human connection” are usually brushed aside as a boomer superiority complex. Fair enough. But let’s try to actually address these claims.

The concept of subcultures as we know it today was first popularised in 1956 by A.K. Cohen’s Delinquent Boys: The Culture of the Gang. In this book, Cohen defined subcultures as a “social space, morality, and social bonds” formed by groups. Then in the mid 60s, the Birmingham School Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies (CCCS) described working-class subcultures as “evidence of symbolic resistance to the mainstream consumption imperative of capitalism”. In 1979, Dick Hebdige claimed that subcultures can also refer to groups of people who share common art, beliefs, morals, and behaviour. Finally, in 2005, Shane Blackman said that subcultures are “concerned with agency and action belonging to a subset or social group that is distinct from but related to the dominant culture”.

Distinct from, but related to, the dominant culture. If we follow Blackman’s definition, subcultures are inseparable from the dominant culture. Much like a fruit sprouts from a seed, subcultures sprout from the wider culture. Whether it’s born from a certain aesthetic (like Goth), a response to psychedelic rock (like punk), or an aestheticisation of the Communist Manifesto (like Vapourwave).

Meanwhile, Cohen and Hebdige’s definitions tell us that members of the same subcultures—as we’ve known them so far—frequent the same places, dress similarly, listen to the same music, and share the same vocabulary.

As subcultures appear, the commonalities within them become more and more noticeable: the fashion, the music, the habits and values. These are noticeable as distinct from the wider culture, but they’re always changing. The members simultaneously create and learn these meanings as the subculture evolves.

So if something is always morphing, can it die?

Culture is decentralised, the mainstream is gone

The most common culprit for this subcultural murder is the internet—more specifically, social media.

Let me explain.

The argument that subcultures are dead often comes from those who lived before and after the internet. They follow Cohen’s idea of subcultures. But Bliss Foster dates back subcultures to the 18th Century. He tells the story of the 1774 novel The Sorrows of Young Werter, which became a worldwide phenomenon—or as much of a worldwide phenomenon as was possible in 1774. The book led to many young men dressing, talking, and behaving like the protagonist. Yes, this is less nuanced than our current definition of subcultures, but so was culture as a whole.

Skip forward a few hundred years and we have the internet. It brought new forms of self-expression and a new layer of culture as a whole. It made information, fashion, and entertainment infinitely more accessible. It’s harder to make a statement, because anyone can choose anything any time. And major companies love to hop on that train and tell us what to choose.

“This digital interconnectedness has led to a mix and match of subcultural elements.”

While it’s always been the case that elements of a subculture get co-opted by companies, our increased accessibility to everything made the time between something emerging and it being co-opted almost non-existent. As Mina Le puts it, these things are “often sold to us as a community even when they’re not. (…) This digital interconnectedness has led to a mix and match of subcultural elements”. Many aspects that make up a subculture are now monetised while still being developed, and they get co-opted by fashion brands or record labels in an attempt to be “ahead of the curve”. There’s no time for a subculture to be born anymore.

A common argument for the death of subcultures is that there is no real sacrifice anymore, that this generation isn’t committed. In the past, people people had no choice but to frequent physical spaces if they wanted to participate in a given scene. While this still happens today—just look at skate and surf cultures—it’s on a much smaller scale because we can get the positive reinforcement of being in a scene without leaving our homes.

Because of this, we don’t feel the need to commit to just one scene—or one subculture. Peter Watts writes for Apollo Magazine that “the wide availability of music allows young people to explore sounds across genres and timeframes, which could also disrupt that need for a tribal identity.” But this is only one theory.

I don’t believe we get all the reinforcement. To say that is to say that texting your friend is the same as sharing a coffee with them. What I do believe is that although we feel that we are a part of something, that physical connection is being replaced by an online one—and it’s just not the same. The need to be a part of a community is as old as the human experience itself, and rather than the entire concept of subcultures dying, maybe they’re just changing.

Dead, alive, or new?

Are we holding on to a definition of subculture that’s no longer relevant?

Post-subcultural theorists believe that the way we experience subcultures changed because of mass-consumption, globalisation blurring the lines between cultures, and our constant access to people, places, and products. In line with this, Ayesha A. Siddiqi wrote that “Gen Z is better able to treat culture as a playground with less self-conscious dissonance because it's not as central to their identity formation as it was for [millennials]. For them, digital is the mainstream. And it's disposable. Being 'alternative' doesn't have the same currency since it's an identity accessible to anyone.” We can now take elements of certain subcultures without ascribing fully to all the baggage that comes with it.

What’s now sprouting up are micro-cultures. Louisa Rogers explained how these have “little cohesion beyond a loose look and feel (i.e. no physical locales to meet up in, no uniform musical taste, no unifying political ideology or worldview)”. People are less committed to a specific scene and instead hop between them. And so, the “aesthetic” is born. By having access to so much all the time, we can simply switch from one aesthetic or subculture to the other if we get sick of it.

But maybe it’s not that bad. As TJ Sidhu wrote for The Face, “Rumours of the demise of subcultures are wangingly exaggerated. They’re everywhere, and you don’t even have to look that hard—or get off your arse—to find them. They’re in your very pocket, posting Stories on Instagram, selling stuff on DEPOP, shaking up the TikTok algorithms. And out in the real world, today’s youth are occupying spaces of their very own, dressed like they belong to something you wouldn’t understand.”

“Being ‘alternative’ doesn’t have the same currency since it’s an identity accessible to anyone.”

Let’s go back to that idea of sacrifice—the mourners of this subcultural demise claim that because we are less committed to subcultures now, they’ve died altogether. But is a subculture less sacred because the barrier to entry is lower? Is gatekeeping an inherent part of subcultures? Or is the internet a way to introduce people to subcultures that they couldn’t find before—and that feels more authentic to them—or does it lead to a superficial, inauthentic performance of it? Are we living in a world of… *gasp* posers?

On the other hand, it does make sense to hold one’s subculture so close to their heart. After all, it creates a sense of belonging among those who otherwise feel a sense of “otherness”. A shared identity is often considered the most important characteristic of a subculture. And letting someone in who “doesn’t get it” could shake up the sanctity of these communities. So gatekeeping is a way for the subculture to protect itself, and the internet has made this nearly impossible.

Maybe specific subcultures have indeed died because they were a product of their time. But to say that the concept as a whole is dying is to say that the human need for connection is dying too. As the internet brings new layers to culture, it does the same to subcultures. Because they exist as a reflection of the wider culture, so they cannot die.